VELOS

A nuestro alrededor fluye una infinidad de imágenes que es vestigio del mundo, rastro de lo real que sin cesura posible penetra la mirada: si el mundo es fuego, las imágenes son humo y son ceniza. Ni representación ni duplicación sino presencia, lo que llama- mos imágenes son cosas del mundo al igual que las calles, las montañas y los árboles, al igual que las nubes, las siluetas de los cuerpos y el vidrio esmerilado.

Vivir en este ecosistema de imágenes, que así como surgen, brotan y emergen también ocultan, encubren y velan aquello de lo real que componen y que las compone, nos ha llevado a ingeniar métodos, técnicas, artilugios y estrategias que nos adapten a su flujo constante y que, consagrándolas, modificándolas, interviniéndolas, interpretándolas, las adapten a nuestra forma distorsionada de percibir el mundo y sus cosas, a nuestra insis- tente vocación de aprehenderlo por la mirada, de imaginarlo tal cual como se prende a nuestro cuerpo y se desprende de él según su sentido incalculable.

Uno de esos múltiples ingenios de lo visible es el velo.

El velo es un viejo artilugio que deja ver cómo la mirada no produce las imágenes sino que son las imágenes las que, alterando las formas de lo sensible, producen la mirada. Allí donde terminan las imágenes comienza la mirada y allí donde termina la mirada comienza el flujo incandescente de las imágenes. Pero hay un espacio, minúsculo, menos que microscópico, nanodimensional, en que imágenes y mirada se confunden hasta ser lo mismo. Ese microtopos es un punto de exaltación donde se posa la mirada sobre el mundo. Un climax aún sin revelar, apenas una marca, huella de un paso que todavía no ha sido dado.

El velo, figura que retoma esta serie de Juan Pablo Velasco, es una sustancia fantasma- górica, una materialidad invisible que modifica la visiblilidad y que no solo trata de ocultar la mirada sino, a través del ocultamiento, de extenderla, de ampliar la visión más allá de sus límites; de persuadirla y habilitar que en ella entre y se adentre lo mirado y su sombra. El velo, tal y como aparece en esta serie, perturba la orientación y el sentido de la mirada, desviándola, poniéndola en riesgo, embadurnándola, desestabilizándola y, con ello, volcándola hacia nosotros.

Así, el velo con el que toda mirada cubre el mundo es, además de ilusión, espejo. Un espejo que desafía lo visible ya que no solamente devela el mundo sino, más que nada, se planta en él, sobre él. El velo, que en esta serie muchas veces es dorado, hace evidente un disimulo y con ello evidencia también una ostentación. El velo, tecnología espectral, encubre, resguarda, arrulla secretos, construye memorias y desvirtúa olvidos. Es el tejido que al cubrirnos nos deja ver más allá de nosotros mismos, haciéndonos ausentes. Es aquello que nos revela la mirada y el afuera, que nos permite avanzar hacia el mundo y que permite también que el mundo avance hacia nosotros y nos penetre, sin atenuan- tes, por los ojos.

Aún así, las imágenes de la serie Velo, que son ilusión y son memoria, nada tienen que ver con una revelación o un develamiento. Son, por el contrario, una forma de entregar lo sensible que persiste en el enigma de la naturaleza de lo visible al exponer la trama con que toda mirada teje las cosas en el mundo.

Texto. Simón Henao

VEILS

Infinity of images flow around us, a vestige of the world, a trace of the real that penetrates the gaze without censoring: if the world is fire, the images are smoke and ash. Neither representation nor duplication but presence, what we call images are things of the world just like the streets, mountains and trees, like clouds and the silhouettes of bodies.

Living in this ecosystem of images -which just as they arise, sprout and emerge also hide, conceal and veil what is real that they compose and that compose them- has led us to devise methods, techniques, gadgets and strategies that adapt us to their flow constant and that, devoting to them, modifying them, intervening them, interpreting them, we adapt them to our distorted way of perceiving the world and its things, to our insistent vocation to apprehend it by looking at it, to imagine it as it is attached to our body and detaches itself from it according to its incalculable sense.

One of those multiple invention of the visible is the veil.

The veil (or Velo in Spanish) is an old object that shows how the gaze does not produce the images but rather the images that, by altering the forms of the sensible, produce the gaze. Where the images end, the gaze begins and where the gaze ends, the incandescent flow of images begins. But there is a space, tiny, less than microscopic, nano-dimensional, in which images and gaze are confused until they are the same. Those microtopes are a point of exaltation where the gaze rests on the world. A climax yet to be revealed, just a mark, a trace of a step that has not yet been taken.

The veil, a figure that takes up this series by Juan Pablo Velasco, is a phantasmagorical substance, an invisible materiality that modifies visibility and that not only tries to hide the gaze but, through concealment, to extend it, to broaden the vision beyond of its limits; to persuade and enable to enter and go deeper to the gaze and its shadow. The veil, as it appears in this series, disturbs the orientation and the sense of the gaze, diverting it, putting it at risk, smearing it, destabilizing it and, with it, overturning it towards us.

Thus, the veil with which every gaze covers the world is, in addition to illusion, a mirror. A mirror that defies the visible since it not only reveals the world but, more than anything, is planted in it, over it. The veil, which in this series is often golden, makes evident a dissimulation and thus also shows an ostentation. The veil, spectral technology, conceals, protects, lulls secrets, builds memories and distorts the oblivion. It is the fabric that by covering us allows us to see beyond ourselves, making us absent. It is what the gaze and the outside reveal to us, which allows us to move towards the world and which also allows the world to move towards us and penetrate us, without extenuating circumstances, through the eyes.

Even so, the images in the Velo series, which are illusion and memory, have nothing to do with a revelation or an unveiling. They are, on the contrary, a way of surrendering the sensitive that persists in the enigma of the nature of the visible by exposing the weave with which every gaze hatches things in the world.

FALSOS PARAÍSOS

La nueva serie de fotografías Falsos Paraísos de Juan Pablo Velasco es una fuerte reflexión sobre la dualidad entre el deseo como impulso para conseguir objetivos y el concepto Budista del deseo como causa del sufrimiento humano. Su práctica no es solamente una crítica sobre el consumismo, sino una búsqueda personal sobre su relación conflictiva con el deseo, y sobre como la vida diaria de una persona puede ser el paraíso de otra. Velasco usa técnicas de montaje digital y collage para representar esta búsqueda, donde se puede ver como la arquitectura y el paisaje se mezclan con la gente, reflejando su propio concepto de paraíso. Los tonos cálidos, que se dan por el material en el que está impresa la obra, dan una sensación de soñar despierto que unifica la serie.

De acuerdo al Budismo, el deseo causa sufrimiento porque nos hace vivir dentro de nuestras cabezas y no nos enfocamos en el presente. Esto quiere decir que vivimos en tiempos inexistentes: el pasado, que no es real porque ya pasó, y el futuro, que tampoco es real porque no puede ser predicho. El deseo también nos hace infelices porque siempre nos hace querer mas de lo que ya tenemos, generando frustración por no alcanzar estos otros paraísos. La intención de Velasco con esta serie de fotografías es reflejar algunos de esos otros deseos y paraísos que creamos en nuestras cabezas. También busca mostrar como este concepto Budista choca con la forma en que la sociedad contemporánea ve el deseo como una promesa de un mejor futuro. En una sociedad de consumo se estimula siempre tener más, consumir y desear algo que no tenemos: más dinero, vivir en una ciudad mas grande o tener un cuerpo diferente para poder ser feliz. Es lo que SS el Dalai Lama define como deseos insensatos, los cuales siempre tienen un límite: ‘Y cuando alcanzas ese límite, entonces pierdes la esperanza, caes en depresión. Ese es uno de los peligros inherentes a esa clase

de deseo.’ 1 Las fotografías de Juan Pablo Velasco también muestran como algunas personas ya viven en esos Falsos Paraísos que queremos alcanzar, sin darnos cuenta que tal vez ya vivamos en el paraíso de alguien más.

Para revelarnos estos Falsos Paraísos, Velasco utiliza montajes fotográficos y collages. En ellos se puede ver una exploración personal sobre sus propios deseos, lo que el quiere lograr y lo que el quiere para un mundo mejor. En series anteriores, Velasco ha utilizado estas técnicas para comunicar un mundo interno más profundo, es como si la realidad de la imagen fotográfica pura no fuera suficiente para representar lo que está en su mente.

En sus series pasadas Ciudades Infinitas y Fragmentos de Ciudad, el ha usado la arquitectura como punto de inicio para crear sus imágenes. En esta nueva serie, Velasco también aprovecha la arquitectura para crear geometrías e integrar personajes humanos en sus composiciones. La arquitectura y los paisajes se convierten en un vehículo para representar su concepto de la dualidad del deseo. La experiencia del artista en la fotografía comercial y el diseño gráfico en publicidad le dan una mirada particular que se manifiesta en la composición estéticamente perfecta de sus collages. Sin embargo, se puede ver que los retratos que combina en sus imágenes tienen un acercamiento a la fotografía documental.

El uso del color también es importante en el nuevo trabajo de Velasco. Las imágenes de Falsos Paraísos están hechas en tonos cálidos, que producen una sensación de ensueño en el espectador, reforzando el concepto de la serie y unificando las diferentes imágenes. Estos tonos se dan al estar impresas sobre placas de metal dorado. Estas placas están hechas para reflejar también al espectador, es una forma de involucrarlo en la obra y hacerlo parte de ella, como

Si fueran un personaje más de sus montajes. Esto es muy importante para Velasco, para él la obra no está completa hasta que el espectador se vuelve parte de ella.

El trabajo de Juan Pablo Velasco tiene un fuerte atractivo visual y conceptual. Sus meditaciones sobre la dualidad del deseo están basadas en una investigación profunda, que se ve reflejada en cada una las obras y como quiere representar su concepto. Estéticamente las imágenes por si mismas son poderosas, la serie se consolida en términos de composición y color, mostrando una evolución en el trabajo de Velasco.

1 Howard C. Cutler HH Dalai Lama, The Art of Happiness (Adelaide, Australia: Hachette Australia, 2013). p 28.

Texto: Daniel Gardeazabal

FALSE PARADISES

Juan Pablo Velascos’s new series of photographs, False Paradises, is a strong reflection on the duality between desire as a propeller to achieve goals, and the Buddhist concept of desire as cause of all suffering. His practice it is not only a critique of consumer society, but rather a personal enquiry on the troubles of desire, and how someone’s daily life can be another person’s paradise. Velasco uses digital montage and collage techniques to portray this quest, where it can be seen how architecture and landscape merges with people, reflecting their inner thoughts and concepts of paradise. The warm tonal range, given by the material the works are printed in, brings a daydream sensation that unifies the series.

According to Buddhism, desire causes all suffering because it makes us live inside our heads and not focus on the present, which means that we are living in non-existing times (the past, which is not real because it already happened, and the future, which is not real either because it cannot be predicted). Desire also makes us unhappy because it makes us always want something more than what we already have, generating frustration for not reaching these other paradises. Velasco’s intention with this series of photographs is to portray some of those other desires and paradises we create in our own heads. It also intends to show how this Buddhist concept clashes with how contemporary society sees desire as a promise for a better future. In a consumer society it is encouraged to always have more, to consume and to desire something we do not have: more money, to live in a larger city or to have a different body to be happy. It is what HH Dalai Lama defines as unreasonable desire, which always has a limit: ‘And when you reach that limit, then you’ll lose hope, sink down into depression, and so on. That’s one danger inherent in that type of desire.’ 1 Juan Pablo Velasco’s photographs also show how some people already live in those false paradises we want to achieve, without realising that we might already be living in someone else’s paradise.

In order to reveal this False Paradises, Velasco uses photographic montages and collages. In them it can be seen a personal insight into his own desires, what he wants to achieve, what he wants for a better world. In previous series, Velasco has used these techniques to communicate a more profound and inner world, it is as if the reality of the raw photographic image was not enough to represent what is on his mind.

In his past series Infinite Cities and Fragments of a city, he used architecture as a starting point to create his images. In this new series, Velasco also draws upon architecture to create geometries and integrate human characters into his compositions. Architecture and landscape photography are become a vehicle to represent his concept on the duality of desire. The artist’s background in commercial photography and graphic design in advertisement gives him an edge on the perfectly composed aesthetics of his collages. Although, it can be seen that the portraits he merges into his mindscapes have a more documentarian approach.

The use of colour is also important on Velasco’s new work. The images found in False Paradises are made in warmer tones, giving a dream-like sensation to the viewer, reinforcing the series’ concept and unifying the different images. These tones are given by being printed on metal plates that resemble gold. The golden plates are meant to reflect the viewer while they are seeing the work, as a way of involving the spectator and including them within the work, as one of the characters seen in his montages.

This is of crucial importance for Velasco, for him the work is not finished until the viewer becomes part of it.

Juan Pablo Velasco's work has a strong visual and conceptual appeal. His reflections on the duality of desire are based on thorough research, evident in each of his pieces and in how he aims to portray his concept. Aesthetically, the images themselves are powerful; the series solidifies in terms of composition and color, showcasing an evolution in Velasco's work.

1 Howard C. Cutler HH Dalai Lama, The Art of Happiness (Adelaide, Australia: Hachette Australia, 2013). p 28.

Text: Daniel Gardeazabal

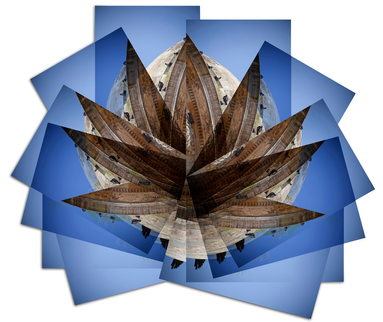

CIUDADES INFINITAS

Las ciudades son la obra colectiva más grande que ha hecho el ser humano, crecen constantemente y entre todos las transformamos. A diferencia de los ecosistemas que se han creado en la naturaleza que están en constante armonía, las ciudades viven en un cierto grado de caos, que al observarlo detenidamente tienen muchos patrones de los cuales parte mi obra, con la que busco que las ciudades puedan seguir creciendo, dándoles otra dimensión con el fin volverlas eternas, infinitas.

INFINITE CITIES

The focus point is the vision of the city as the biggest collective masterpiece of mankind, since it is constantly growing and transform by every human being in it. Unlike the harmonious ecosystems found in nature, cities live in constant chaos, chaos that if you look close enough makes patterns that are the start point of my work. I want to capture these patterns to give the cities a new dimension so they can be eternal, infinite